Blood is an essential part of the body's composition. Blood is the very element of life itself. The flow and offering of blood represent the pain of life. Blood is the material visibility of invisible pain. Blood is also a marker of temporality, and this is especially true for women, as it represents the monthly menstrual flow and the surging of life. Additionally, blood is the gush of life at birth, which always brings more blood and pain for the mother.

In this sense, blood is the most intimate element for women. Blood is the beginning of self-awareness for women, yet it brings a kind of non-knowledge because it is an intimate experience of individual life that cannot be shared. "I cannot feel the pain in your feet." Pain cannot be shared, so why express one's pain if it is impossible to share such feelings? The pain of blood poses a fundamental challenge to art, as the external manifestation of art is meant to be communicable and shareable. If pain is a private life sensation, and art does not convey such sensations, then how can art have a universal resonance? Or perhaps, art in visual form may not necessarily express such bodily suffering, just as the poet and philosopher Ji Kang (嵇康) of the Wei (魏) and Jin (晋) dynasties said, "Sound is devoid of sorrow or joy." The volume and pitch of music are not directly associated with human joy or pleasure. The same piece of music can be said to convey joy by some and pain by others. It is not directly related to the sound itself. What is it related to then? If an artist wants to express their pain in their work and allow viewers to share their pain, how is that possible?

This is why an artist must find a unique material that is related to their own body and their existence as a living being. Just as traditional Chinese painting uses ink as a material because of its inherent connection to writing, it can regulate one's breathing. Just as calligraphy requires a certain posture and breath, and ink achieves a sense of ethereal atmosphere, it can adjust one's thoughts and state of being. The material is connected to the body, the material is connected to the image, and the imagery once again returns to the artist's body. Therefore, it must start from one's own body.

For a female painter, to convey her own pain, she should start from her own body. For her, the most experienced moments of pain are when blood flows, when the body is scratched and hurt. Yes, that is to paint with her own "blood." Let the painting have the taste of the blood of life!

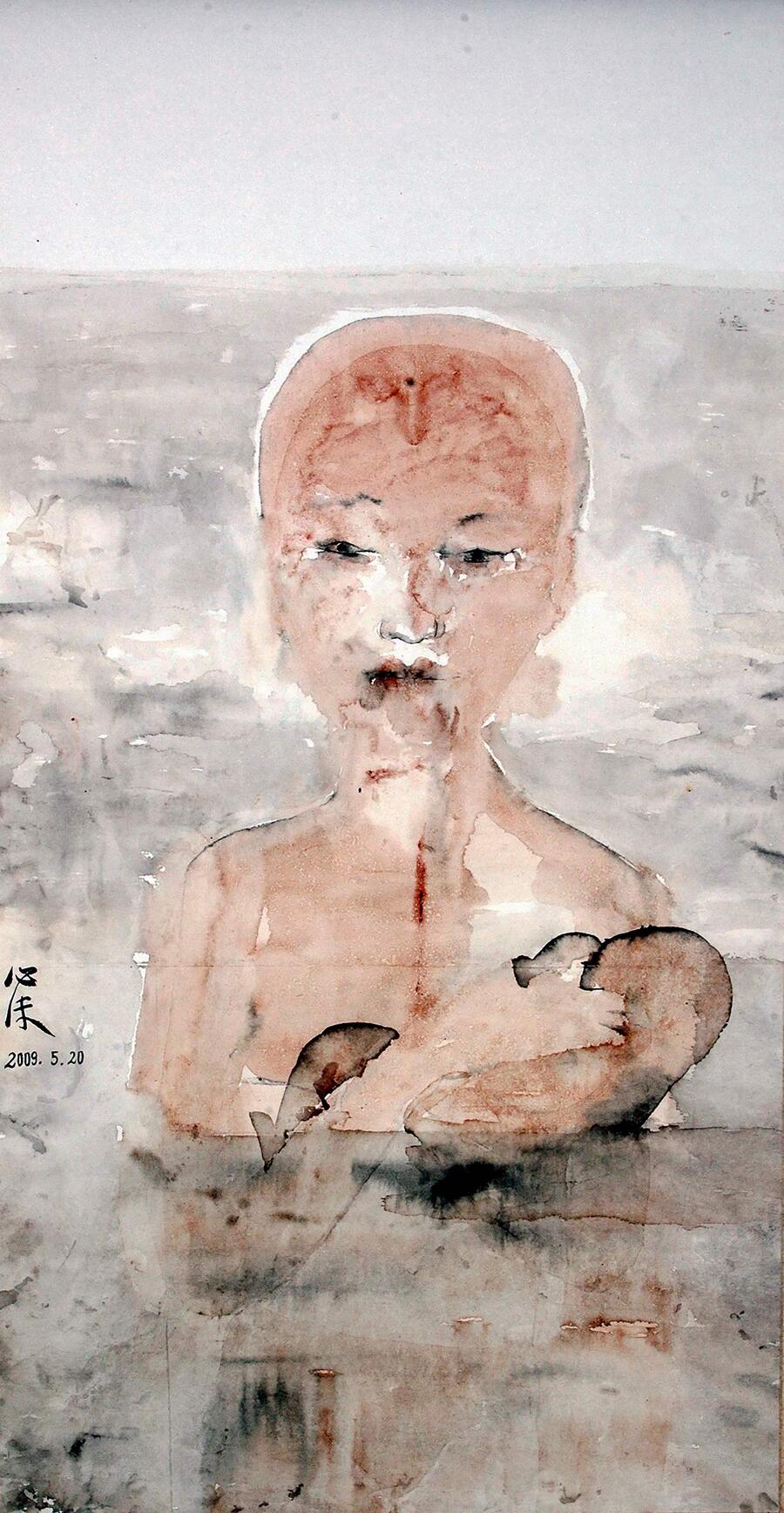

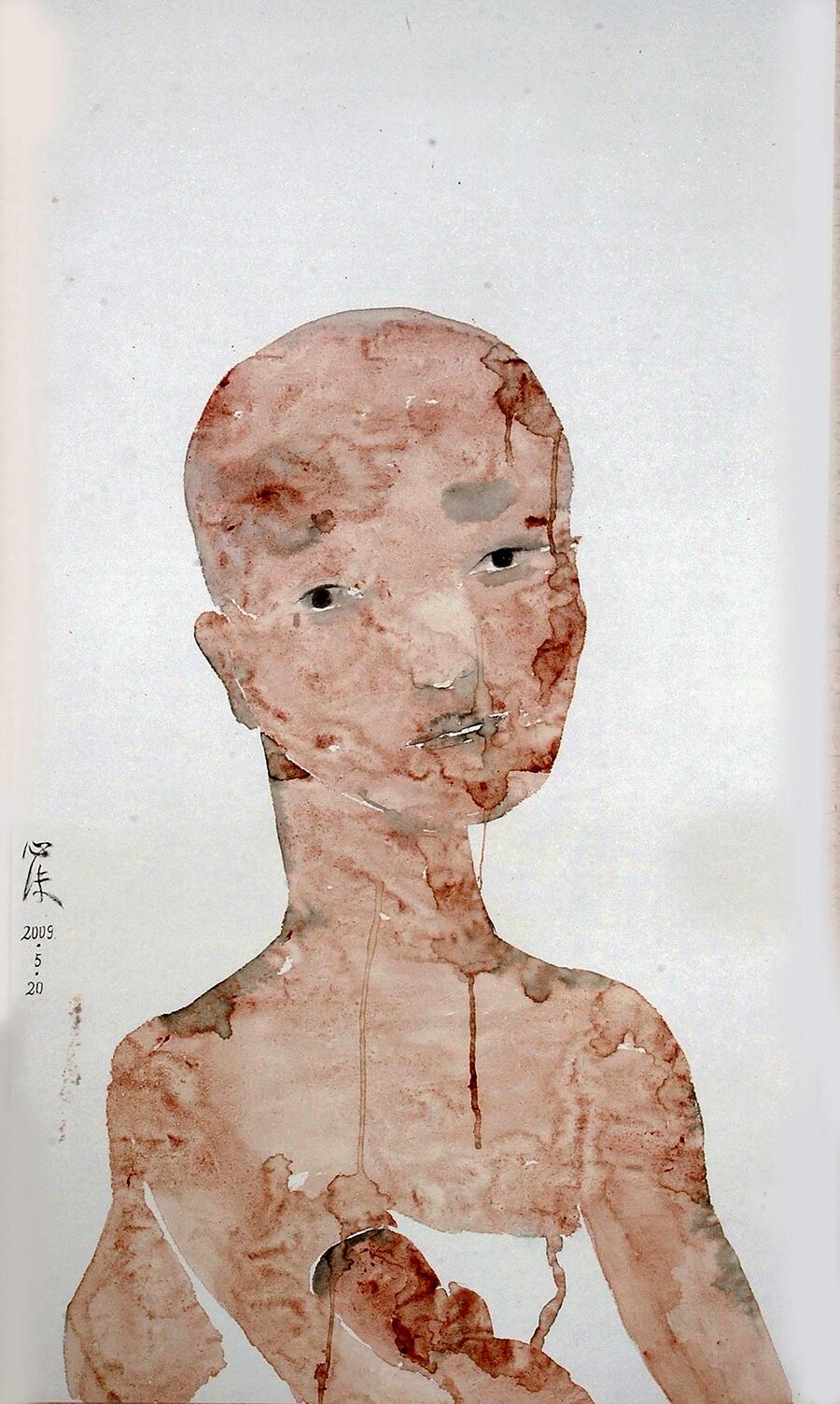

And this is the new beginning of the recent works of the female artist and painter Li Xinmo: she paints self-portraits using her monthly menstrual blood. It's not about intentionally shedding blood for a violent shock effect, nor is it about deliberately seeking new materials. Instead, it is about letting nature itself act on a woman's life, using blood—the rhythm of life that creation bestows upon a woman's life—to create art! Although there have been performance artists using blood, using menstrual blood to paint self-portraits is almost a first in the history of painting! It adds the taste of life to the painting, which is related to not only the lingering charm of traditional Chinese aesthetics but also the writing of individual life, capturing the taste of remaining life. It is in the taste that life touches itself and stimulates the senses of others!

Li Xinmo, as a painter in her prime years, had previously worked with ink painting, and her ink works were already very well executed. Whether it was the simplicity and lightness of her ink strokes or the vividness of her character portrayals, coupled with her insight into calligraphy and its modern transformation (her work "Leek Flower Paste" has already been published), one could see her talent and technique. She could have continued down the conventional path of ink painting that was popular at the time. However, as she fully immersed herself in contemporary life, she discovered that the so-called ink art of today lacked true contemporaneity. It merely used traditional ink language to depict some modern themes, merely expanding on subject matter without undertaking a thorough reevaluation of ink painting concepts, techniques, and the possibilities inherent in ink itself. It was merely a collage, combining Western modern emotional and conceptual ideas with traditional ink techniques, without genuinely harnessing new techniques and concepts driven by contemporary life conditions. This was because artists fundamentally failed to question: What constitutes the contemporaneity of art?

Is ink painting defined solely by its materials? Is it just a genre of painting? When ink language first emerged, why was ink chosen over gold and green materials? It was chosen to convey a sense of atmosphere. Whether it was in depicting snowy landscapes, water scenes, or the ethereal phenomena of dissipating clouds and vanishing smoke, ink's materiality could better fulfill these artistic aspirations. Only when the "material" used (ink and silk paper), the "object" or image depicted (mountains, waters, smoke, and clouds), and the spiritual "mood" portrayed (tranquil as water and ancient as smoke) all achieved internal coherence did ink language gain legitimacy and fully develop its own language. Just as gold was used in medieval Western art: as both a material pigment and as a symbol of halos above saints' heads, or as a representation of the divine radiance, all three aspects converged. Subsequently, Western classical painting techniques like perspective and chiaroscuro opened up a container to embrace the symbolic space of the divine (as articulated by art historian Panofsky). Western modernist art also inherited these three elements but with modifications: using the pigment itself as an expressive material facing the chaotic and formless (where pigment was not just a tool but the most expressive essential entity), depicting the current life state of the object itself and the relationship between the painter's physical state or posture while painting (as seen in Pollock's drips and Freud's depiction of the model's current exhaustion), and the experiences of inner strength or powerlessness in life (an experience of the individual's existential void and meaninglessness).

In contemporary Chinese society, can ink, as a material, still embody its traditional sense of tranquility? If mixed materials are introduced, what is the spiritual aspiration? Can the object depicted with ink convey the traditional essence of tranquility and the meandering rhythm of life that it seeks to achieve? What relationship does the depicted object have with the material? Clearly, current ink works have not addressed these fundamental questions.

Once Li Xinmo delved deeper into contemporary art and the conditions of individual life, her focus on female life itself, the wounds of the female body, and the unfortunate fate of women began to manifest in the form of images. For example, in "Wounds on My Body," she documented the traces of injury. In "The Vagina Monologue," she contemplated violence, and in works like "A Solo Wedding," she imagined the folds of the female body, and the female body emerged as an independent subject in her art. For Xinmo, she must contemplate: What is the relationship between the body of the artist painting and the objects she wishes to paint? Why use the language of ink painting?

Therefore, she had no choice but to introduce her individual sense of time into her works. Contemporary Chinese art, especially in recent years, has stagnated because it has lost a tangible sense of time. The artworks from the 1990s that resisted ideological constraints still possessed a sense of rebellion in the contemporary context. However, today, they often only hold commercial display value. It's not just a matter of the temporal aspect of images; it's also about the individual's sense of time, as well as opening up the spatial and temporal dimensions within the artwork. Only when these three dimensions of time are simultaneously conveyed within the artwork can a painting truly become a testament to the finite existence of an individual life.

Xinmo's self-portrait in her artwork represents the contemporary "ink painting." Similar to Foucault, who was inspired by Baudelaire's reflections on art in his essay "What is Enlightenment?" and believed that contemporary or modern aesthetics of existence has several key elements. These elements included the heroic representation of the discontinuous time passing in the present (capturing the eternal in the now, rather than departing from the contemporaneity of the present). This heroization also had an element of self-irony (attempting to imagine a present different from itself and altering its appearance). This inevitably led to a form of asceticism in the guise of a dandy who loved fashion (because he had to create himself, forcefully make himself according to his own standards), and thus, this self-creation could only occur in art, which is the artistic transformation of everyday life. This is also the formation of what Foucault referred to as the aesthetic style of modern existence. Additionally, it's important to introduce another element: the traditional Chinese aesthetic understanding of individual life cultivation and self-care. Of course, in his later work, Foucault also recognized the importance of the techniques of self-care. Therefore, the measure of the contemporaneity of Chinese art lies in the ways of experiencing and conveying the current moment.

In Li Xinmo's works, we see these factors: she is both an artist and a keen critic, both an inheritor of traditional calligraphy and painting and a practitioner of contemporary experimental art. Her personality has both an intense and resolute side as well as a tender and self-loving aspect (her highly decorative self-portraits, inspired by the Virgin Mary, reveal her gentle and affectionate side). However, in the subterranean experience of pain, more of her heroic side as a woman emerges—her questioning of traditional authority, her bold actions, and her experiments with imagery all reveal her love and concern for contemporary life. What she loves is this shattered present, the present filled with her own body. This is evident in the moment of menstrual blood flow each month, in the midst of pain. But it must be written with the passion of art, and this is the self-portrait.

To paint with her menstrual blood is undoubtedly a thorough embodiment of asceticism. Women often dread their menstrual blood, and each monthly period is undoubtedly a torment for women, whether it's the amount of blood or the timing. It leaves their bodies and mental states fatigued and disordered, marking a pause in life, an interruption of rhythm. Therefore, inscribing this moment is also inscribing one's own catastrophe, achieving self-confirmation and the redemption of loneliness through artistic creation.

This is also an individual life's memory of the universe, a way for women to experience the eternity of nature in their unique way. Perhaps, in our era, it is only the female body that retains a passive memory of natural rhythms. This is why contemporary thought begins with gender differences—the differences between women and men in terms of gender and body—rather than ontological differences as the most fundamental point of departure!

In a woman's menstrual blood, she undergoes a certain kind of assault by nature, which is an experience of the passivity of life. Now, when Xinmo transforms her menstrual blood into an element of painting, it directly connects the material of painting with her own body, giving the painting a certain personal scent. If ink was once associated with the gentleness and tranquility of traditional Chinese literati, now it appears too feeble. Or rather, there is a need to find a new relationship between ink and her own body, as Xinmo primarily uses blood to paint while still incorporating ink as a material.

What is most striking about Li Xinmo's work is that she captures the essence of life. This is the true flavor of life, and in these very contemporary works, it transcends traditional aesthetics to become intimately connected with the flavor of individual life.

In the artwork, we see a self-portrait sketched with blood, and clearly, she has no hair, and as the bodily form reverts to blood, it appears to be a primitive and primal naked life—a life just born, possessing the simplest essence of life. There is an outline, but it cannot be too specific, as this is the bareness of life, completely stripped down to its form at birth. The eyes and lips in the head are depicted in a traditional outline style, conveying a poignant expression and spiritual focus. In the artwork, we also see the effect of "blood" spreading like ink. Xinmo skillfully transforms the traditional flow of ink into an expression of internal pain. The naked body has some prominent, coagulated blocks of color scattered throughout. These are blood clots formed by the amount of blood and the pauses in her strokes during painting. These details are so realistic, emerging prominently on the pure white rice paper, creating a visually stunning effect that is hard to forget. The artwork evokes endless sorrow and sympathy. As Xinmo herself said, "Thousands of years of suffering have gathered in me!" In the head of the image, you can see the thinker's pain—blood seems to be throbbing in her head, suggesting that this woman experiences physical pain as she thinks.

The signature and date on the artwork are particularly important; they are signed with blood, the most direct marker of time. In Xinmo's self-portrait works, her individual life's time is inscribed. In this portrait, which is both hers and not hers, her life receives self-creation. It is indeed Xinmo's self-portrait, but because of the blood's recontextualization, it becomes an original form of life that belongs to everyone. We are all born in blood, and our lives are composed of it. Therefore, the artist has discovered a universal image of the self or the other! Just as she painted herself in the image of the Virgin Mary, this self-portrait adorned with a crown of thorns, created with silver powder, is pure and serene, plain, and elegant. It is also an imagination and alienation of herself and the self. The essence of contemporaneity lies in the artist's imagination of the self, their love for the passing present, and the rediscovery of the inner life.